Before we get started, I wanted to let you know the third episode of my new podcast Room to Run is live on Spotify and Apple Podcasts.

In this week’s episode we discussed:

Are Democrat or Republican Presidents better for stocks?

Which stock is the next Nvidia (NVDA)?

Preview for the busiest week of the year

Each 10-minute episode can be listened to for FREE on Spotify and Apple Podcasts. If you enjoy the podcast, please leave a review.

It looks like we’re finally getting an interest rate cut this week.

Investors have now priced in a 100% probability that the Federal Reserve will announce an interest rate cut at Wednesday’s Federal Open Market Committee.

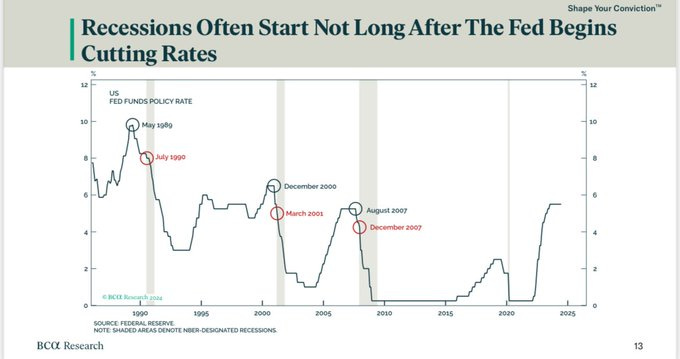

And not everyone is excited. For instance, a few Patreon Portfolio members have sent me this chart showing that interest rate cuts typically happen at the start of recession…

…with strong stock market pullbacks soon following. Mark Spitznagel - who manages $16 billion for Universa - echoed this sentiment, stating:

“The arrival of a Fed rate cut cycle has tended to coincide with a sizable stock-market drawdown.”

However, while it’s true interest rate cuts do coincide with market downturns, you need to put the data into its proper context.

The Raw Data is Damning

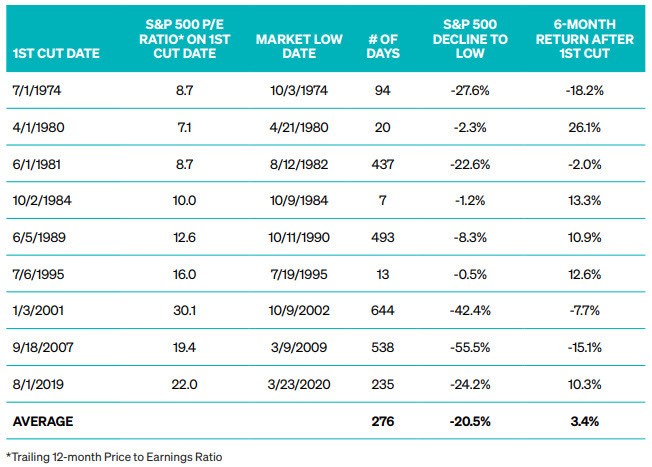

Whenever I mention that lower interest rates will be good for stocks and other risk assets, I always get people in my comments reminding me that stocks historically perform poorly after the first rate cut.

And if you look at the raw data, there is some truth to this.

The S&P 500 has fallen -8% on average after the first rate cut since 1950. We saw this in 1989 when the S&P 500 fell -6% in the three months after the first rate cut. We also saw this in January 2001 when the S&P 500 fell -11% in the six months after the first rate cut. We even saw this in September 2007 when the S&P 500 cratered -20% after the Fed cut rates.

Again, this makes sense when you look at the raw data. But when you put the data into context, it makes sense why this happens. See, when the Federal Reserve cuts interest rates, it’s usually because there’s some sort of problem in the economy.

Lowering interest rates is like a doctor giving medicine to a sick patient—it's usually a sign that something is wrong.

It could also mean that a crisis is already happening. This is what happened in March 2020 when the Fed cut interest rates to dull the effects of the global COVID-19 lockdown. It was the same in 2001 when the Fed cut rates because of the dot-com bubble burst. And in 2007? It was in response to the financial crisis.

But it’s also worth noting that the Fed does not only cut rates in response to a crisis.

Partying Like It’s 1995

Sometimes the Fed cuts interest rates because they deem policy “too restrictive.”

For instance, in 1995 the Fed reduced rates to support a slowing economy and prevent a potential recession, even though there was no immediate financial crisis. Similarly in 2019, the Federal Reserve cut rates three times, citing concerns over slowing global growth and trade tensions. Both of these cuts led to massive rallies in the S&P 500, with the index surging approximately 29% in 1995 and around 28% in 2019 following the rate cuts.

This issue comes back to the classic argument of correlation vs causation.

Yes, the first interest rate cut is correlated with stock market declines. But the cause of these declines is what’s happening in the economy, like the collapse of Lehman Brothers during the 2008 financial crisis or the global COVID lockdowns in 2020… not the rate cuts themselves. It would be like saying medicine made a persons fever worse, even though they were already sick to begin with.

And as we see with 1995 and 2019, interest rate cuts in absence of a crisis is actually extremely bullish for stocks.

Personally, I think our current situation is more akin to 1995 or 2019 and the upcoming cuts will be bullish.

And if my thinking changes, you’ll be the first to know.

Stay safe out there,

Robert